Do you remember your last exit interview? Did you think, “Well, there’s no reason to burn bridges,” and swallow your private criticisms of the company? Or did you tell the HR person interviewing you what the problem was—insufficient pay, family demands, interest in other roles—knowing it was too late to address them?

Exit interviews are designed to triage the causes of employee discontent at just the moment when they’re almost irrelevant. Yet many of the reasons that people quit their jobs are addressable, if managers are open-minded.

Instead, what if companies shifted the conversation from the end of employment to the beginning with an entry interview. Adam Grant—author of Originals, Give and Take, and Option B–is an expert in entry interviews, having implemented them at several companies and written about the topic in Harvard Business Review (HBR). He helped us craft a survey template from the questions he uses personally when he hires someone new.

To ensure our survey would be valuable to as many people as possible, we sent a survey to over 5,500 people to ask about their experiences with entry interviews and see what types of questions make the most impact. One of our leading researchers, Jillesa Gebhardt, analyzed the data and helped apply it to the new survey.

Want to try Adam's entry interview?

Get the free survey template here.

What is an entry interview and how does it help?

As Grant and his co-writers put it, “Most companies design jobs and then slot people into them. Our best managers sometimes do the opposite: When they find talented people, they’re open to creating jobs around them.”

For the past 10 years or so, business leaders have been talking about a concept called “job crafting.” The idea is that employees can slowly prune away the parts of their work they don’t like and introduce parts they prefer by taking on and refusing tasks, building relationships, etc.

But Grant points out that managers usually have a lot more influence—and institutional insight—than their direct reports. Instead of employees hacking their way into work they like better (and possibly burning out in the process), why not collaborate to find an arrangement that’s mutually beneficial?

An entry interview opens the dialog. It should happen quickly after a new hire starts and give managers a framework for making management decisions. The survey, which should be shared before the interview, gives employees space to think about the questions in advance and make notes.

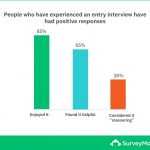

According to our new research, just over half of American workers have had some form of entry interview (56%), and their experiences have been overwhelmingly positive. 85% enjoyed the experience, two-thirds (65%) found it helpful, and another 26% said it was ‘reassuring’. Among the four in ten who have not had an entry interview, 41% would definitely like to have one in their next job and another 40% are on the fence. Less than 11% would prefer not to have one.

Why entry interviews are good for business

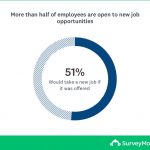

51% of people would take a new job if it was offered to them right now. Discontent is the norm, and with ~4% unemployment, employees can afford to be picky.

Some estimates put the cost of turnover as high as 50-200% of that person’s annual salary—which accounts for lost productivity, recruiting resources, referral bonuses, and so on. Other effects of turnover (like negative morale) are hard to quantify. If entry interviews can help reduce or delay turnover, the benefits are broad.

Entry interviews help managers build jobs that their teams find both interesting and fulfilling, which not only reduces turnover, but also boosts engagement and enthusiasm. People who love their jobs put in more thought, creativity, and—often—innovation than people who don’t.

Entry interviews may also add a secondary layer of value to the business—extra support. According to our research, engagement is not just a question of what employees like and what they dislike. They also want to feel like their skills are being fully utilized.

Among the things that employees wished their managers had asked them were:

- That I'm experienced in much more than what I'm doing now.

- That I am willing to take on any challenge.

- That I speak another language.

In other words, many people in the workforce are willing to work harder, or differently, in ways that could be much more valuable to the business than the tasks they handle currently.

What to ask about in an entry interview, and why it matters

The questions in our template are grounded in trends that came up consistently in our research, along with Grant’s years of research and business expertise. The questions fall under a few different categories, each of which is important in a different way. We structured some of our research questions around findings from Grant’s past research.

In his report for HBR, he and his research partners found 3 factors that more satisfied employees had in common:

1) confidence that they were acquiring new skills

2) enjoyment of their work

3) belief that they were using their strengths

The untapped strengths in #3 could represent a lot of potential for their employers.

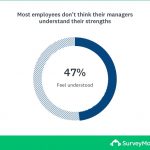

Strengths and passions: Only 47% of newly hired employees in our research felt like their manager fully understood their strengths—dire given Grant’s findings about the relationship between using strengths and preventing turnover. Those Facebook findings were validated across various industries and geographies in a recent Korn Ferry study of over 5,000 professionals, which found that the number one reason that people leave their jobs is boredom.

Our template asks for specific examples of projects that the person loved in the past, what would make them proudest of their career upon retiring, and strengths they’ve never used before. These types of prompts tend to get more expansive responses than generic questions like “list your strengths.”

Goals and motivations: While 76% of managers say they currently understand their direct reports’ motivations well, only 59% of individual contributors agree. Part of that is because “goals and motivations” can mean a plethora of different things. The same person can have dozens of different drivers, professional and personal, at the same time.

Often, chief amongst those goals is a hunger to learn. In Grant’s previous research of satisfied employees, he found that they were 37% more likely to believe they were gaining important skills than their unsatisfied colleagues—an even more dramatic difference than job enjoyment (31%) or strengths usage (33%).

In our survey, we ask about what new skills employees are eager to learn, the muscles they’d like to flex more, and what motivates them. While every employee might not have an answer for every question, they will almost certainly have thoughts for at least one.

Talents and interests outside of their role. New employees might be curious about work in cross-functional teams or have relevant skills for tangential roles. Both came up consistently in our research.

Obviously, you can’t have a salesperson weighing in on legal matters (unless they happen to have a law degree) or an HR person at a hospital treating patients, but realistically most companies have a good deal of flexibility. If a new marketing hire is curious to know more about data science or an accountant might like writing for the blog, their manager can keep an ear out for opportunities for them to do so. These types of explorations can be deeply fulfilling without meaningfully detracting from the employee’s core responsibilities.

Earlier this year we talked to Charu Sharma, the CEO of a mentorship company called NextPlay.ai. Among the learnings that came from working with hundreds of companies (including Lyft, Square, and Coca-Cola) was this insight:

“When mentorship programs start out, the temptation is typically to pair junior members of a certain team or department with more senior leaders in the same space. But we’ve found that asking people about their goals is a better way to do it.

Some of the most valuable relationships we’ve created have been through cross-functional pairings. One salesperson that Nextplay.ai matched with a leader on the product team helped the company identify a million dollar market opportunity. Getting different viewpoints is the best way to create innovative solutions.”

Supporting interest in other teams doesn’t need to mean a transfer—mentorship and minor participation are equally viable ways to support employee growth in the areas they care about.

Learning styles and management needs: Most employees actually have a pretty clear idea of the way that they should be managed. While many people tend to think about managers having different “management styles,” there’s also opportunity for the direct report to shape the relationship by being explicit about their needs and learning styles.

A few excerpts from our research on what employees would have liked to be asked about:

- “What kind of leadership role I would like to take; what type of feedback would help me grow.”

- “The way I learn. Everyone learns differently.”

- “That this (internship) space is a new space for me and I am trying to find my place and my voice, and with that comes a lot of insecurities about whether or not I belong or am doing good work, etc.”

- “That I thrive with consistency. That I sometimes need to be told to take a break.”

- “I'm low maintenance, but not no-maintenance.”

- “I like to work independently.”

- “I like to plan tasks ahead of time.”

Individual preferences can vary, but questions like “do you prefer to work alone or in groups?” and “what makes a good boss?” can be extremely illuminating for new managers.

Personal conditions: Sometimes a small accommodation from a business can have a huge impact on an employee’s quality of life. Giving a person with a chronic illness flexible work hours or someone with a sick parent to the ability to work remotely are gifts that employees really appreciate—many times without creating too much inconvenience.

These types of personal needs were among the most cited “wishlist” items in our research, and they don’t tend to come up organically in workplace environments unless companies give them space to speak up, or employees self-advocate. According to Natasha Walton of the Tech Disability Project:

“When employers enact rigid policies that require all employees to work in a similar way, it...can make disabled employees feel as though they need to hide their disabilities and access needs, putting increased stress on those individuals and preventing them from bringing their whole selves to work.

Many people with disabilities need flexibility when it comes to hours and location, allowing them to work from home if and when they need to, or to go to appointments during the work day. But that’s far from standard, even in roles where the majority of the work is digital.”

Employees don’t know what types of accommodations are available to them unless their managers broach the conversation. Talking about these kinds of things early can sometimes keep personal situations from escalating to the unmanageable. In the midst of a stressful situation, it might seem easiest just to quit. Entry interviews can hopefully help prevent that.

But it’s not just about finding solutions. Many times, even when managers are limited in what they can do to help “fix” the challenge, knowing about it can still help them lead with empathy.

Some personal conditions fall on the other end of the spectrum: outside passions hobbies that might add color to their life in the workplace, too. In HBR, Grant describes a lawyer whose dreams of being a pilot shapes the type of cases he takes on and a teacher who brings a guitar to class. Asking about these outside interests helps managers relate to their team members on a human level—and might even create fun opportunities for bringing those passions to work.

Entry isn’t the end

Even though this survey template is titled “entry interview,”, it doesn’t stop being useful after that initial onboarding conversation. People acquire new skills, reevaluate their goals, and can even develop a new disability over the course of a few months. So instead of closing the conversation after that first interview, we recommend using this template to guide a regular cadence of check-ins.

We recommend that managers and their team members have one of these “job crafting” conversations regularly over the course of the employee’s career; it can even be an extension or restructuring of an existing meeting.

A simple way to do this using the template would be to remove some of the less relevant questions and schedule it to run regularly as a recurring survey.

If you want to benchmark your success, consider using our employee engagement survey to see whether entry interviews make impact. (You can benchmark against your own company, or against results from similar organizations.)

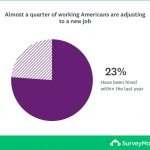

A quarter of American workers are currently in the process of adapting to a new job, having started within the last year (23%), with another 35% reporting to a new manager at their existing company. With so much flux in the workplace, there’s never been a more important time to create workplaces and roles where workers can thrive.

Methodology: This SurveyMonkey poll was conducted online from May 7 - 20, 2019 among a total sample of 5,523 full time and part time employed adults age 18 and over living in the United States. Respondents for these surveys were selected from more than two million people who take surveys on the SurveyMonkey platform each day. The modeled error estimate for the full sample is plus or minus 2 percentage points. Data have been weighted for age, race, sex, education, and geography using the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey to reflect the demographic composition of the United States age 18 and over.